The Sit Down with David Ferguson

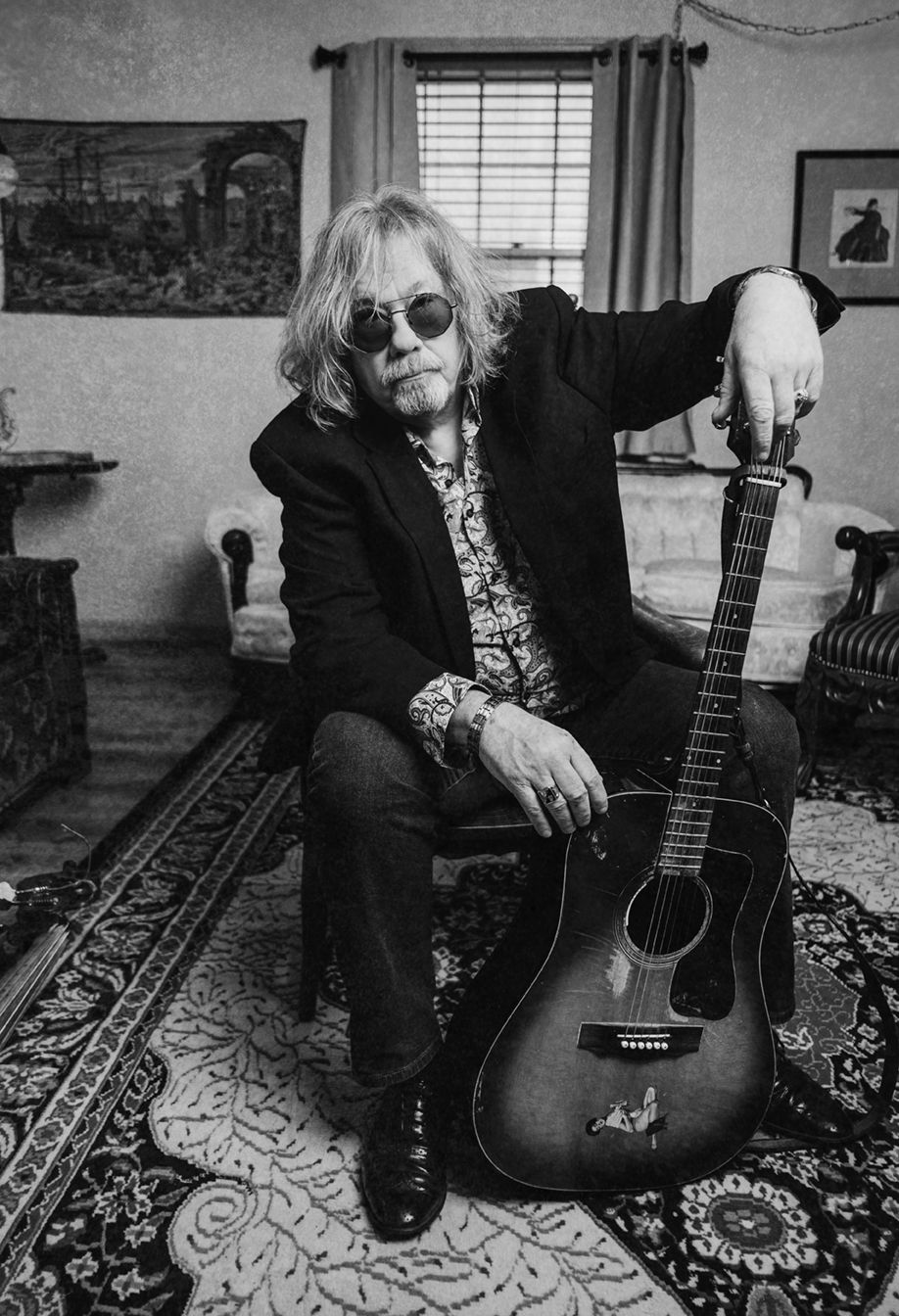

To introduce David Ferguson, you can’t add much more than the words of Sturgill Simpson: “The Ferg is a bonafide card-carrying legendary hillbilly genius and when he talks you better shut up and listen. He's played bass for Jimmy Martin, chopped tape for Cowboy Jack Clement, been called a dear friend by Johnny Cash and John Prine, recorded every one of your damn heroes at least twice, and he's forgotten more about music, specifically recording music, than you'll ever know in your entire existence. So...next time you start thinking your shit doesn't stink just stop and look in the mirror and ask yourself, ‘I'm sorry and you'll have to excuse me but...is your name David Ferguson?”

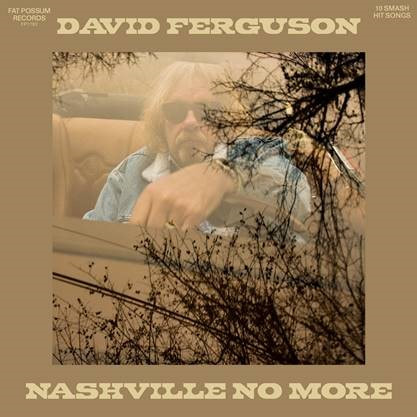

This Grammy Award winner has pretty much done everything and worked with everyone through a career lasting four decades. He has worked with icons such as Johnny Cash, John Prine and Sturgill Simpson but always from behind the scenes but now Ferguson comes front and centre with the release of his first album as a recording artist. “Nashville No More” will be released on September 3rd through Fat Possum (available HERE) that will feature the absolute who is who of music city including Margo Price and Bluegrass power couple Sierra Hull & Justin Moses. Jamie had the pleasure of meeting “The Ferg” over Zoom to hear all his stories and about this long overdue project.

Releasing a record that is your own for the first time rather than being involved with someone else’s must feel a bit different and a more holistic process where it doesn’t just stop when it has been mastered?

“I don’t normally have to think about it much after it’s done so it’s somebody else’s problem after I’ve done all my damage but it’s been fun and I’ve been enjoying it. I’ve been recording and been in bands for a long time but a few years ago back in 2012, I did a little record of all Jack Clement songs. It wasn’t released commercially much but that was a nice little record and I did that when I was on tour with a girl called Anna Ternheim just so I would have something to sell at the shows. This one came about over a pretty long period of time. I had a recording studio in Nashville called The Butcher Shoppe and they sold the buildings that it was in so when I knew it was coming, here at my place in Goodlettsville about twelve miles north of Nashville, I had an outbuilding that I built onto and put a control room and a little overdub booth into where I could mix. During the pandemic, there was no work in Nashville so I just walked out to my little control room every day and started digging out a bunch of old recordings that as I didn’t have anything else to do, I finished them off. I played them for my friend Matt Sweeney who went nuts over it and sent it to the guys at Fat Possum who called me up and said we want this thing, so that’s what happened.”

Was it strange working with musicians and producing your record during the pandemic compared to how things had been previously?

“I wanted to get used to my new little control room and stuff but really there was no work for anyone for about six months and people were pretty afraid to get out so a lot of the musicians and other singers on the record , I had sent it to them so were overdubbed over the internet but Margo (Price) came here to the Butcher Shack as I call it and a few of the other guys did too.”

From when you started in the eighties, you must have seen the way creating and recording music has substantially evolved?

“I’ve seen a lot of formats since I’ve been doing this! When I started, digital wasn’t here yet and it was all analogue. Then in the mid-eighties, there was the first multi-track digital machine which was crazy and a sophisticated piece of equipment that was really expensive. We went through some digital formats: there was the eight-track, then the cassette and cd’s so things have progressed to where you can now take a laptop and a microphone then make a record if you know what you’re doing.”

This Grammy Award winner has pretty much done everything and worked with everyone through a career lasting four decades. He has worked with icons such as Johnny Cash, John Prine and Sturgill Simpson but always from behind the scenes but now Ferguson comes front and centre with the release of his first album as a recording artist. “Nashville No More” will be released on September 3rd through Fat Possum (available HERE) that will feature the absolute who is who of music city including Margo Price and Bluegrass power couple Sierra Hull & Justin Moses. Jamie had the pleasure of meeting “The Ferg” over Zoom to hear all his stories and about this long overdue project.

Releasing a record that is your own for the first time rather than being involved with someone else’s must feel a bit different and a more holistic process where it doesn’t just stop when it has been mastered?

“I don’t normally have to think about it much after it’s done so it’s somebody else’s problem after I’ve done all my damage but it’s been fun and I’ve been enjoying it. I’ve been recording and been in bands for a long time but a few years ago back in 2012, I did a little record of all Jack Clement songs. It wasn’t released commercially much but that was a nice little record and I did that when I was on tour with a girl called Anna Ternheim just so I would have something to sell at the shows. This one came about over a pretty long period of time. I had a recording studio in Nashville called The Butcher Shoppe and they sold the buildings that it was in so when I knew it was coming, here at my place in Goodlettsville about twelve miles north of Nashville, I had an outbuilding that I built onto and put a control room and a little overdub booth into where I could mix. During the pandemic, there was no work in Nashville so I just walked out to my little control room every day and started digging out a bunch of old recordings that as I didn’t have anything else to do, I finished them off. I played them for my friend Matt Sweeney who went nuts over it and sent it to the guys at Fat Possum who called me up and said we want this thing, so that’s what happened.”

Was it strange working with musicians and producing your record during the pandemic compared to how things had been previously?

“I wanted to get used to my new little control room and stuff but really there was no work for anyone for about six months and people were pretty afraid to get out so a lot of the musicians and other singers on the record , I had sent it to them so were overdubbed over the internet but Margo (Price) came here to the Butcher Shack as I call it and a few of the other guys did too.”

From when you started in the eighties, you must have seen the way creating and recording music has substantially evolved?

“I’ve seen a lot of formats since I’ve been doing this! When I started, digital wasn’t here yet and it was all analogue. Then in the mid-eighties, there was the first multi-track digital machine which was crazy and a sophisticated piece of equipment that was really expensive. We went through some digital formats: there was the eight-track, then the cassette and cd’s so things have progressed to where you can now take a laptop and a microphone then make a record if you know what you’re doing.”

How did you first get involved with the technical side of music and what drew you to engineering and production?

“I always wanted to do it, even when I was young. When I was young, I always knew I wanted to do something to do with the technical end of it but I’m not really a very technical person, I don’t really know much about electronics but I can run the equipment. I always wanted to do it and I had the opportunity when I went to work for Jack (Clement) to learn how to operate a recording studio. He really encouraged me and sent me to a couple of different technical schools because he said if you’re going to make records for a living, you have got to know something. He spent his own money and paid me by the hour, so when I was working for him during the day, part of my day was to go to a couple of classes. Belmont college was right down the street from the studio and I did some courses down there which was kind of fun.”

Jack Clement was obviously such an influential figure in your career and someone you worked with extensively but how did you first meet and form that relationship?

“I worked for Coley Coleman at a music store in Nashville called the Old Town Pickin’ Parlour. It was an instrument repair place and all the bands that would come through town dropped their instruments off to be set up for whilst they are in town. Then that closed and the owner went to work for Jack doing video production and stuff because Jack was video crazy, which I’m glad he was because he left a legacy of some beautiful footage. I got a call from Coley saying there was an opening for somebody to run errands, make coffee and stuff so asked was I interested? I said shoot yeah anything! I was working construction at the time which I didn’t mind because I was young but that’s how I got in over there. I started in 1982, I think and basically stayed there and worked for Jack until he died.”

Whilst he was a mentor to you, you actually got to portray Jack Clement on the big screen too:

“Yep, I played him in Great Balls of Fire! Dennis Quaid was Jerry Lee then Jack knew Dennis and got wind that they were making this movie about Jerry Lee. Jack called up Dennis, we went to Memphis and hung out with Dennis. Dennis got me a reading for that part with the director and he took me and read with me. The big-time actor doesn’t ever do that unless they want somebody to be in the movie and he did, so he helped me get the part and it was fun as hell, it was a ten-week party!”

Over the years you have worked with some of the biggest names in music but Johnny Cash is obviously the one that really stands out as an iconic figure and musical legend:

“Johnny was the greatest, he was a really good friend. I started working with him at Jack’s and everything he could possibly get me on, he did. We were good friends and he helped me a lot, I was really loyal to John and Jack, loyalty means a lot in this business but Johnny was a great and funny guy.”

Through the projects you were involved in with Johnny, you also worked with Rick Rubin. Was this the first time you had collaborated alongside him?

“Johnny was on Mercury records then when he got off that we heard he had signed a deal with Rick Rubin on Def American and was working with Rick. Rick came to town to work with Johhny at the cabin and Johnny called me saying Ferg you’ve got to get over here right now, Rick Rubin’s here and we don’t know how to turn on the equipment! I busted ass out there and turned it on for them and showed them how to run it. When he came back, we recorded a bunch of stuff with Richard Dodd who is a famous British engineer that lives here now and does most of the mastering for almost everybody’s records here. Richard and I set up the recording out there, it was a little more difficult , we didn’t have a remote truck as that would have been the easy way to do it but then Rick asked me if I wanted to go to LA to finish the record because he knew John really liked me and he could communicate with John through me. I did that several times and went out there for really long stretches of time to work on these records.”

“I always wanted to do it, even when I was young. When I was young, I always knew I wanted to do something to do with the technical end of it but I’m not really a very technical person, I don’t really know much about electronics but I can run the equipment. I always wanted to do it and I had the opportunity when I went to work for Jack (Clement) to learn how to operate a recording studio. He really encouraged me and sent me to a couple of different technical schools because he said if you’re going to make records for a living, you have got to know something. He spent his own money and paid me by the hour, so when I was working for him during the day, part of my day was to go to a couple of classes. Belmont college was right down the street from the studio and I did some courses down there which was kind of fun.”

Jack Clement was obviously such an influential figure in your career and someone you worked with extensively but how did you first meet and form that relationship?

“I worked for Coley Coleman at a music store in Nashville called the Old Town Pickin’ Parlour. It was an instrument repair place and all the bands that would come through town dropped their instruments off to be set up for whilst they are in town. Then that closed and the owner went to work for Jack doing video production and stuff because Jack was video crazy, which I’m glad he was because he left a legacy of some beautiful footage. I got a call from Coley saying there was an opening for somebody to run errands, make coffee and stuff so asked was I interested? I said shoot yeah anything! I was working construction at the time which I didn’t mind because I was young but that’s how I got in over there. I started in 1982, I think and basically stayed there and worked for Jack until he died.”

Whilst he was a mentor to you, you actually got to portray Jack Clement on the big screen too:

“Yep, I played him in Great Balls of Fire! Dennis Quaid was Jerry Lee then Jack knew Dennis and got wind that they were making this movie about Jerry Lee. Jack called up Dennis, we went to Memphis and hung out with Dennis. Dennis got me a reading for that part with the director and he took me and read with me. The big-time actor doesn’t ever do that unless they want somebody to be in the movie and he did, so he helped me get the part and it was fun as hell, it was a ten-week party!”

Over the years you have worked with some of the biggest names in music but Johnny Cash is obviously the one that really stands out as an iconic figure and musical legend:

“Johnny was the greatest, he was a really good friend. I started working with him at Jack’s and everything he could possibly get me on, he did. We were good friends and he helped me a lot, I was really loyal to John and Jack, loyalty means a lot in this business but Johnny was a great and funny guy.”

Through the projects you were involved in with Johnny, you also worked with Rick Rubin. Was this the first time you had collaborated alongside him?

“Johnny was on Mercury records then when he got off that we heard he had signed a deal with Rick Rubin on Def American and was working with Rick. Rick came to town to work with Johhny at the cabin and Johnny called me saying Ferg you’ve got to get over here right now, Rick Rubin’s here and we don’t know how to turn on the equipment! I busted ass out there and turned it on for them and showed them how to run it. When he came back, we recorded a bunch of stuff with Richard Dodd who is a famous British engineer that lives here now and does most of the mastering for almost everybody’s records here. Richard and I set up the recording out there, it was a little more difficult , we didn’t have a remote truck as that would have been the easy way to do it but then Rick asked me if I wanted to go to LA to finish the record because he knew John really liked me and he could communicate with John through me. I did that several times and went out there for really long stretches of time to work on these records.”

It's so fascinating to hear these stories about all these wonderful people that you got to work with:

“It’s much more interesting from afar! Really when you are working on stuff like that, you don’t really think about it being that way because you’re just busy. I always knew that working at Jack’s as an engineer and his protégé was the best job in the world. I knew I had the best job in the world and I thought about it that way. I miss him, I miss the old boy.”

Moving back to talking about your record, how was it to work on fine tuning your own project sitting in the producer’s chair when it was on your own recording?

“Sooner or later you have gotta call it done! Anybody that has ever made a record themselves know that it’s hard. It is very difficult to go out and listen to yourself, nobody wants to listen to themselves and most people don’t even recognise their voice if you play it back to them, they say who is that? People don’t really enjoy listening to themselves and I don’t enjoy listening to me but what I did learn to do and I think this is a good piece of advice for anybody who is going to make a record by themselves, is that you need to look at like you’re listening to somebody else because that’s the only way you can really be objective so you don’t really think about it being you. You get overly critical and get insecure about whether it sounds in tune or this and that. One day you listen to it and it sounds OK and the next day you are like this sounds like shit, so you go through a lot of that back and forth tail chasing until you say that it is what it is. I was really just making a little record for my mom; I was just going to give it to her but I sent it to Matt and to the mastering guy who said there’s a few things you need to touch up and that helped a lot, Richard Dodd helped a lot. It’s just hard to be objective, it’s a tough thing to do and anybody that has done it will tell you that it’s tough and that’s why most people don’t produce themselves. It’s all in my lap. When you’re making a record for somebody else, first of all they have got to trust you because you’re the ears. Producing yourself takes a lot of time and usually takes a lot of money, if I would have had to pay for the studio time it took to make that record, I could have bought a house. I was lucky enough to have unlimited studio time and an engineer at my disposal the whole time, ME! I’m responsible for it, it’s my name up front and as producer. It’s kind of the wrong thing to do for a guy in my position because somebody may hear it and think well if he can’t do no good on that for himself? You have to contend with everything but I think there is some stuff on there that people will enjoy. It’s not a bashing record, it’s a soft record, it’s a record that a sixty-year-old man would make.”

Finally, what was the idea and inspiration for calling the album “Nashville No More”?

“It’s a line from “Knocking Around Nashville” that I don’t go knocking around Nashville no more. The title really reflects that the Nashville I knew and grew up in is no more, it’s gone and it isn’t coming back. I’m not saying that it’s a bad thing, change happens and Nashville is more like New Orleans now than New Orleans is. I mean it’s insane down there on Broadway, there’s thousands of people down there every night in those bars and drinking in the back of trucks and busses. It’s become a real tourist attraction, it always was a tourist attraction because of country music but country music now is more like pop. Today’s country sounds like yesterday’s rock and roll, someday the formats will meld together I think but the format I do totally approve of and I’m glad that we have now is Americana. It’s bluegrass, it’s roots music and Americana can be anybody, it’s a way for people to hear your music and this is probably the first time in the history of recorded music that this has happened in the last few years with stations popping up and it has a Billboard chart which is good! It doesn’t necessarily mean just American music, there’s this lady Yola and she’s British. She makes her records right over here on eighth avenue with Dan Auerbach, she’s really nice and I was around for a little bit of that when he was working on it, especially the first one. She’s great, she knocks an audience of her feet and this latest record of hers is doing really well. Then you’ve got Sturgill’s bluegrass and the other stuff that he does which is all in that format so it’s wonderful.”

“It’s much more interesting from afar! Really when you are working on stuff like that, you don’t really think about it being that way because you’re just busy. I always knew that working at Jack’s as an engineer and his protégé was the best job in the world. I knew I had the best job in the world and I thought about it that way. I miss him, I miss the old boy.”

Moving back to talking about your record, how was it to work on fine tuning your own project sitting in the producer’s chair when it was on your own recording?

“Sooner or later you have gotta call it done! Anybody that has ever made a record themselves know that it’s hard. It is very difficult to go out and listen to yourself, nobody wants to listen to themselves and most people don’t even recognise their voice if you play it back to them, they say who is that? People don’t really enjoy listening to themselves and I don’t enjoy listening to me but what I did learn to do and I think this is a good piece of advice for anybody who is going to make a record by themselves, is that you need to look at like you’re listening to somebody else because that’s the only way you can really be objective so you don’t really think about it being you. You get overly critical and get insecure about whether it sounds in tune or this and that. One day you listen to it and it sounds OK and the next day you are like this sounds like shit, so you go through a lot of that back and forth tail chasing until you say that it is what it is. I was really just making a little record for my mom; I was just going to give it to her but I sent it to Matt and to the mastering guy who said there’s a few things you need to touch up and that helped a lot, Richard Dodd helped a lot. It’s just hard to be objective, it’s a tough thing to do and anybody that has done it will tell you that it’s tough and that’s why most people don’t produce themselves. It’s all in my lap. When you’re making a record for somebody else, first of all they have got to trust you because you’re the ears. Producing yourself takes a lot of time and usually takes a lot of money, if I would have had to pay for the studio time it took to make that record, I could have bought a house. I was lucky enough to have unlimited studio time and an engineer at my disposal the whole time, ME! I’m responsible for it, it’s my name up front and as producer. It’s kind of the wrong thing to do for a guy in my position because somebody may hear it and think well if he can’t do no good on that for himself? You have to contend with everything but I think there is some stuff on there that people will enjoy. It’s not a bashing record, it’s a soft record, it’s a record that a sixty-year-old man would make.”

Finally, what was the idea and inspiration for calling the album “Nashville No More”?

“It’s a line from “Knocking Around Nashville” that I don’t go knocking around Nashville no more. The title really reflects that the Nashville I knew and grew up in is no more, it’s gone and it isn’t coming back. I’m not saying that it’s a bad thing, change happens and Nashville is more like New Orleans now than New Orleans is. I mean it’s insane down there on Broadway, there’s thousands of people down there every night in those bars and drinking in the back of trucks and busses. It’s become a real tourist attraction, it always was a tourist attraction because of country music but country music now is more like pop. Today’s country sounds like yesterday’s rock and roll, someday the formats will meld together I think but the format I do totally approve of and I’m glad that we have now is Americana. It’s bluegrass, it’s roots music and Americana can be anybody, it’s a way for people to hear your music and this is probably the first time in the history of recorded music that this has happened in the last few years with stations popping up and it has a Billboard chart which is good! It doesn’t necessarily mean just American music, there’s this lady Yola and she’s British. She makes her records right over here on eighth avenue with Dan Auerbach, she’s really nice and I was around for a little bit of that when he was working on it, especially the first one. She’s great, she knocks an audience of her feet and this latest record of hers is doing really well. Then you’ve got Sturgill’s bluegrass and the other stuff that he does which is all in that format so it’s wonderful.”

|

Nashville No More Tracklist:

Four Strong Winds Boats to Build Fellow Travelers. Nights With You Looking for Rainbows Chardonnay Early Morning Rain Knocking Around Nashville My Autumns Done Come Hard Times Come Again No More David Ferguson released his debut album as a recording artist “Nashville No More” on September 3rd through Fat Possum Records which is available HERE. |

True country music is honesty, sincerity, and real life to the hilt.

Garth Brooks

|

|

Proudly powered by Weebly